Journal

Improving alternative text for images

Some colleagues at work have recently been asking interesting questions about “good/appropriate alternative text for images”. I definitely reckon it’s a topic worth revisiting because it feels like the landscape has changed a bit on this front over the years.

I think the web design industry has traditionally been:

- lacking knowledge of how to write good alternative text.

- too quick to decide which images are “purely decorative”, or accurately described by a matter-of-fact short label when maybe they actually should convey their inherent tone and emotion to all users rather than only those with no visual impairments.

But as inclusion-centric practioners we can probably do better. In his blog post Writing great alt text Jake Archibald breaks down the considerations. I reckon it’d be useful for us to dissect this post and try to boil it down to some practical rules-of-thumb for our teams.

But also, I’ve just noticed a couple of interesting developments at the big players. Firstly, Twitter have upped their image alt game and are encouraging their users to try doing so, too.

And hot on the heels of Twitter’s announcement, I now see in Slack an Edit file details option for adding image descriptions. It’s great that Twitter and Slack are doing this… and also serves as a reminder that tools such as Slack and Twitter are consumed on the web and so accessible best practices apply when you’re writing content on them, too!

SVG: collected tips

SVG is an amazing technology which I regularly use for icons and occasionally for logos and illustrations. I’ve also dipped my toe into animated SVG. But if I’m honest I still find some SVG concepts confusing so I’ve gathered some useful tips here for future reference. Note: this is a living document which I’ll expand over time.

Table of contents

- Introduction to SVG

- Canvas, viewport and viewbox

- Arranging elements on a grid

- Inline SVG for icons

- Choose an SVG embedding technique that suits the task

- Choose the best-performing format

- Exporting and optimising SVG in design tools

Introduction to SVG

It’s an image format (like jpg and png) but also an XML-based markup language. So it’s a bit like HTML in that you can “compose a whole from a bunch of parts” – but it is focused on graphics. As a web graphics technology it has many benefits, for example:

- scalable,

- manipulable by CSS and JS,

- has a small file-size if well-optimised, and

- can be made accessible.

- It’s built for drawing in a way HTML and CSS are not.

- It can guide users, reduce their cognitive load, and provide personality and moments of fun.

Here’s a classic example: Log-in Avatar

Canvas, viewport and viewBox

Let’s break down the key elements of the SVG coordinate system.

Canvas

The canvas is the area where the SVG content is drawn. It’s infinite in both dimensions therefore the SVG can be any size.

Viewport

Although the canvas is infinite, the SVG is rendered on the screen relative to a finite region known as the viewport. Areas of the SVG that lie beyond the boundaries of the viewport are not visible. This is similar to a browser viewport. On a long page you don’t see all the content; just a portion of it.

Specify the viewport size by giving your <svg> element a width and height, e.g.:

<svg width="600" height="400">

<!-- svg content -->

</svg>We could specify units (such as em or px) but don’t need to. Unitless values are regarded as being set in user space using user units which effectively equate to pixels so our example above renders a 600px by 400px viewport.

The width of the viewport can also be set in CSS. Setting width:100% makes the SVG viewport fluid in a given container.

Viewbox

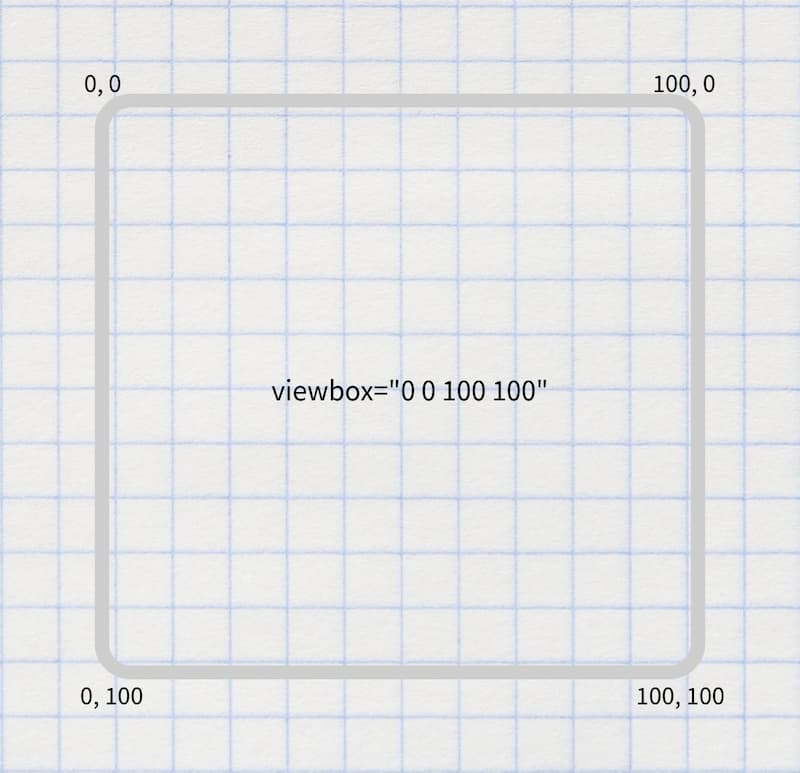

The viewport coordinate system starts at the top left (0, 0) corner of the SVG viewport. The user coordinate system is by default identical to that of the viewport, starting in the same place and with equal dimensions and units, however it can be modified using the viewBox attribute.

viewBox takes a value in the format: x y width height. The first two values set the upper-left corner of the viewbox and the second two its dimensions.

You can set the aspect ratio of the viewbox to the same as for the SVG viewport, or differently.

You might (optionally) use the viewBox attribute to transform the SVG graphic by scaling or translating it, or to crop it.

Specifying a smaller viewbox than viewport results in cropping the graphic to those dimensions and then zooming it in i.e. scaling it up so that it fills the entire viewport area.

Arranging elements on a grid

Cassie Evans recommends that when planning an arrangement of elements it’s nice to start with a simple grid using nice round numbers such as 100×100 – per the following <svg> – making it easy to then plot elements on top. You might even start by sketching with paper and pencil.

<svg viewBox="0 0 100 100">

<!-- svg content, perhaps <rect>s -->

</svg>

Inline SVG for icons

Having tried various icon systems including using <symbol> and <use>, Chris Coyier advocates that it’s perhaps simpler and better to just include the icons inline. Perhaps use the appropriate include technique for your stack to keep the code maintainable.

Choose an SVG embedding technique that suits the task

There are a variety of flavours and uses of SVG, including:

- icons

- infographics

- illustrations

- SVG that include text

- SVG that include animation.

As Sara Souidean covers in her talk “A Smashing Case Study”, your choice of SVG embedding technique depends on the nature of the project and the specific use case.

To do: summarise Sara’s technique for SVG with illustration and accessible text.

Choose the best-performing format

When you’re tasked with coding an illustration-based image, it’s tempying to automatically see that as a job for SVG. However keep in mind that for some images the SVG file size will be massive and PNG will perform much better, so compare the two options.

Exporting and optimising SVG in design tools

To export an SVG in Figma, right-click it (or select it on the left hand side) then select “copy as SVG”. There’s also an “export as SVG” option on the right.

References

- Understanding SVG Coordinate Systems by Sara Soueidan

- Swipey image grids by Cassie Evans

- A pretty good icon system by Chris Coyier

- A Smashing Case Study recorded presentation by Sara Souidean

Web Components with Declarative Shadow DOM via Lit and Eleventy

Here’s a new development in the Web Components story, and one that may have positive implications for resilience, performance and progressive enhancement.

Declarative Shadow DOM is a new way to implement and use Shadow DOM directly in HTML rather than by constructing a shadow root in JavaScript.

But some people including Chris Coyier and Brad Frost) reckon that writing that looks horrible. Brad said:

Declarative Shadow DOM always looked gross to me and I felt it almost defeats the purpose of web components.

And Chris added:

the server-side rendering story for Web Components, Declarative Shadow DOM, doesn’t feel very nice to me if you have to do it manually.

However Lit, a library which makes working with Web Components easier, are now providing ways to make this easier when Lit is used with Eleventy.

With tools like this (especially this @lit-labs/ssr project), we can have our cake and eat it too: use web components in a dev-friendly way, and then have the machines do the heavy lifting to convert that into a grosser-yet-progressive-enhancement-enabled syntax that ships to the user.

using JavaScript frameworks in an entirely-client-side rendered way isn’t nearly as good for anything (users, SEO, performance, accessibility, etc) as server-side rendering (the effects of hydration are still debatable, but I view as largely worth it) … [but] the server-side rendering story for Web Components, Declarative Shadow DOM, doesn’t feel very nice to me if you have to do it manually. So… don’t do it manually! Let Eleventy do it!

As an additional footnote, perhaps we can make frameworks other than Eleventy (such as Rails) create server-rendered custom elements with Declarative Shadow DOM in a similar way. One to explore.

Minimum Viable Web Component (by Zach Leatherman)

Zach tweeted last year to share a codepen which illustrates the very simple boilerplate needed for a minimum viable web component. Note: his example is so simple that in this case the JavaScript isn’t actually needed for the custom element to work, however the provided JS is a starting point for when you do actually intend to add JS-driven features.

The HTML:

<foo-component>Hello, world</foo-component>The CSS:

foo-component {

font-size: 4em;

}The JS:

customElements.define("foo-component", class extends HTMLElement {

constructor() {

super();

// Add your custom functionality.

}

});I’ve started, so I’ll panic: what it’s really like to go on Mastermind (on The Guardian)

When Mastermind comes on TV, Clair and I always enjoy competing against each other to see who’s most intelligent / least stupid and always jokingly say we’d fancy our chances in real life (although we really wouldn’t). So I enjoyed Sirin Kale’s amusing memoir on what it’s really like to get in the famous black chair!

It is spotlit, well worn, imposing. Its leather has been burnished by the arses of minds far greater than mine, minds capable of retaining all manner of trivia while staying cool under pressure and not panic-sweating profusely via their bum cheeks on to the seat; cellulite-free grey matter, crammed full of general knowledge like a suitcase you have to sit on to close. My mind, by comparison, is a duffel bag containing a single pair of socks.

GOV.UK visitor stats for January 2022

Thanks once again to Matt Hobbs and GOV.UK for sharing their website visitor stats publicly so that we can learn from them. As ever, lots of juicy detail in Matt’s thread.

GOV.UK stats for January (1-31):

- Chrome - 45.08%

- Safari - 36.82%

- Edge - 7.38%

- Samsung Internet - 7.08%

- Firefox - 1.35%

- Android Webview - 0.72%

- Safari (in-app) - 0.61%

- Internet Explorer - 0.5%

100% = 187,969,863

—Matt Hobbs, @TheRealNooshu

In particular, their “usage by device type” stats see mobile at ~67%, Desktop at ~30.5%, Tablet at ~2.5%.

In terms of comparative traffic, according to Simliar Web’s Top 10 most visited UK websites list they’re hovering around #10.

Skip to Content: Online Accessibility Insights from Léonie Watson

Here’s a lovely, short (13 min) interview from an accessibility expert with a really positive outlook—highly recommended.

Q: What’s just one thing that every single person can do in the progression toward an accessible internet?

A: When you’re talking to colleagues, peers… promote the notion that accessibility is just part of what we do because we’re good at our job. It’s not extraordinary, it’s not unusual, it’s not something you can drop because you’re pushing for launch.

Division and construction in design systems

Over the last couple of days I’ve been watching an interview with Brad Frost on Storybook’s channel. I’m still only halfway through but it’s great so far.

One part I’m loving is, from about 25 mins in, when Brad talks abut how Atomic Design crucially includes the notion of not only “breaking interfaces down” (like every DS does) but also “building them back up”. It’s not just the atoms and molecules that are important, but also combining them into (in Atomic Design parlance) organisms and templates, too. For example when using Storybook as an internal workshop (in my team our equivalent is LookBook), he makes a point of it not just including components but also templates, so that:

we can internally test with a high degree of confidence before handing over to our user-consumers that when our components are assembled together, they work”.

I like the idea of our workshop containing not just components but also multicomponent arrangements, or even full page templates. It’d mean less need to go arrange this stuff in the consuming application all the time. Brad’s chat also chimes with some recent thoughts I’ve been having about Patterns and also a tweet from Heydon Pickering regarding a catalogue vs a system.

Essentially, I think that in component libraries, notions of hierarchy and composition are really important. Simply having “a catalogue of components” (including lots that are common to all Design Systems) might not hugely separate your library from Bootstrap or Material. However it’s our ability to combine our custom legos into specific higher order arrangements, and our care for making sure they combine together harmoniously that creates our own special sauce.

My talk, “Hiding elements on the web” for FreeAgent’s tech blog

I recorded a talk on “Hiding elements on the web” for @freeagent’s tech blog. It’s a tricky #FrontEnd & #a11y topic so I try to cover some good practices and responsible choices. Hope it helps someone. (Also it’s my first video. Lots of room to improve!)

---What open-source design systems are built with web components?

Alex Page, a Design System engineer at Spotify, has just asked:

What open-source design systems are built with web components? Anyone exploring this space? Curious to learn what is working and what is challenging. #designsystems #webcomponents

And there are lots of interesting examples in the replies.

I plan to read up on some of the stories behind these systems.

I really like Web Components but given that I don’t take a “JavaScript all the things” approach to development and design system components, I’ve been reluctant to consider that web components should be used for every component in a system. They would certainly offer a lovely, HTML-based interface for component consumers and offer interoperability benefits such as Figma integration. But if we shift all the business logic that we currently manage on the server to client-side JavaScript then:

- the user pays the price of downloading that additional code;

- you’re writing client-side JavaScript even for those of your components that aren’t interactive; and

- you’re making everything a custom element (which as Jim Neilsen has previously written brings HTML semantics and accessibility challenges).

However maybe we can keep the JavaScript for our Web Component-based components really lightweight? I don’t know. For now I’m interested to just watch and learn.